Did you know the Blessed Mother appeared to St. Thérèse of Lisieux?

And did you know, when St. Thérèse was a girl, she suffered nearly nine months of demonic torments? And that her healing or freeing from these attacks coincided with this apparition of the Blessed Mother?

This was the apparition of Our Lady of the Smile.

The Martin's family statue of the Blessed Mother smiled at St. Thérèse.

And, did you know this statue and the Miraculous Medal were based on the same statue that was destroyed in the French Revolution?

And did you know this also connects to the feast of Our Lady of Victory?

And did you know this appearance of the Blessed Mother to the child Thérèse also foreshadowed Mary's appearance to the shepherd children of Fatima?

You've got to read about this!

Catholic Near-Death Experiences

By the way, this is just a small section of a book I am writing on Catholic Near-Death Experiences that will be published this year by Sophia Institute Press

Stay tuned for more on that ...

Read St. Thérèse's Autobiography, Story of a Soul

Much of the following is excerpts from St. Thérèse's Autobiography, Story of a Soul. I have published an edition of this book with photographs taken by St. Thérèse's sister, as well as study guide questions. Follow the links below to buy a copy:

The Month of October, Where Coincide the Feasts of St. Thérèse, Our Lady of Victory, and Our Lady of the Smile

October is an auspicious month for St. Thérèse of

Lisieux, and an important month for the Blessed Mother, as well.

We celebrate October 1 as the feast of St. Thérèse—this

is very near the date of her death September 30, 1897. October 2 was also a

significant day to St. Thérèse. It was on this day in 1882 that her second

mother, her sister Pauline, entered the Carmelite monastery. It was on this

same day—perhaps because the devil could not abide the thought of two Martin

sisters entering the monastery and all the future defeats this would mean—that

10-year-old Thérèse fell deathly and mysteriously ill.

St. Thérèse describes her illness as the devil’s retribution

in her autobiography, Story of a Soul.[1]

This

suffering so affected me that I soon became seriously ill. The illness was

undoubtedly the work of the devil, who, in his fury at this first entry into

the Carmel, tried to avenge himself on me for the great harm my family was to

do him in the future.

October 7 is

the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary, which was originally named Our Lady of

Victory. This feast commemorates the Battle of Lepanto of 1571. The whole of

Christian Europe joined in praying the Rosary to protect the combined Christian

navies of the Holy League, which were significantly outnumbered by the Muslim

fleet. It was a decisive victory for the Church, and Pope Pius V instituted the

feast of Our Lady of Victory. This marked the high-water mark of Muslim power

and expansion in the Mediterranean.

These are all very big, complex, and world-sized

events. Far too big for the Little Flower, it seems. So St. Thérèse planted a

little flower beside the great oaks of these world events, a special,

additional, though little-known feast for the Blessed Mother on October 7.

This is the story of how the Blessed Mother

received the title of Our Lady of the Smile. As St. Thérèse wrote in Story

of a Soul, “A miracle was necessary, and it was Our Lady of Victories who

worked it.”

The Nature of the Sickness

On October 2, 1882, St. Thérèse’s dearest sister Pauline

entered the Carmelite monastery. After the death of their mother (now St.)

Marie-Azelie, Pauline had been Thérèse’s second mother. Thérèse was only 4

years old when her mother died, and now it seemed, she was losing her mother

all over again.

|

| Saints Marie-Azelie and Louis Martin |

Thérèse did not yet know the “joy of sacrifice” and suffering, so her pain at this parting was intense. She wrote:[2]

How

can I describe the anguish I suffered! In a flash I saw life spread out before

me as it really is, full of sufferings and frequent partings, and I shed bitter

tears.

Pauline’s entrance into the monastery seemed to

bring on incurable physical and mental torments for young Thérèse. Thérèse

began to suffer terribly, but it was not for just one or two weeks. It was

months.

The sickness began with comnstant headaches. These

intensified as winter approached, leading to shivering, convulsions,

hallucinations, pains, and lack of appetite.

St. Thérèse’s doctors, including psychiatrist Dr.

Marie-Dominique Fouqueray, were baffled by the young girl’s disease.[3]

Thérèse’s sister Marie, who never left her side through her torments, recalled hearing

the doctor’s prognosis after observing one of the girl’s strange fits. The

doctor said there was nothing science could do for the child. No treatment

helped.

There was no respite from her torments, except for

one day, April 6, 1883. It was the day Pauline received her habit at Carmel. It

was also Eastertide.[4]

The Little Flower had been suffering for nearly seven months at this

point.

St. Thérèse describes this day in her autobiography

and makes it clear that there was no merely natural origin to her illness:

On

reaching home I was made to lie down, though I did not feel at all tired; but

next day I had a serious relapse, and became so ill that, humanly speaking,

there was no hope of any recovery.

I do

not know how to describe this extraordinary illness. I said things which I had

never thought of; I acted as though I were forced to act in spite of myself; I

seemed nearly always to be delirious; and yet I feel certain that I was never,

for a minute, deprived of my reason.

Sometimes

I remained in a state of extreme exhaustion for hours together, unable to make

the least movement, and yet, in spite of this extraordinary torpor, hearing the

least whisper. I remember it still. And what fears the devil inspired! I was

afraid of everything; my bed seemed to be surrounded by frightful precipices;

nails in the wall took the terrifying appearance of long fingers, shriveled and

blackened with fire, making me cry out in terror. One day, while Papa stood

looking at me in silence, the hat in his hand was suddenly transformed into

some horrible shape, and I was so frightened that he went away sobbing.

But if

God allowed the devil to approach me in this open way, Angels too were sent to

console and strengthen me. Marie never left me, and never showed the least

trace of weariness in spite of all the trouble I gave her.

The nature of St. Thérèse’s sickness appeared to be

supernatural in origin. Though she was been harassed by the devil, she was not

possessed. Another one of Thérèse’s sisters, Céline Martin, who later became Sister

Geneviève of Saint Teresa, provided testimony evidencing this point. Witnessing

her sister’s sufferings, Céline noted, “However, unlike with illnesses caused

by the devil, pious objects never frightened her.” Demonstrating revulsion to

holy or blessed objects is a tell-tale symptom of demonic possession.

That St. Thérèse was suffering from demonic harassment,

however, appears clear. St. Thérèse’s cries of distress were terrifying to all those

around her.

St. Thérèse’s sister Marie never left her side.

Like Pauline, Céline, and Thérèse, Marie also later became a religious, taking

the name Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart.

Sister Marie was asked to provide testimony for

the beatification and subsequent canonization of St. Thérèse. Regarding this

period, Sister Marie testified that, although Thérèse never lost her ability to

reason, she experienced “terrifying visions that gave chills to all those who

heard her cries of distress.”

Sister Marie described that during some of the

incidents, “Her eyes, which were usually so calm and gentle, had an expression

of terror in them that is impossible to describe.”

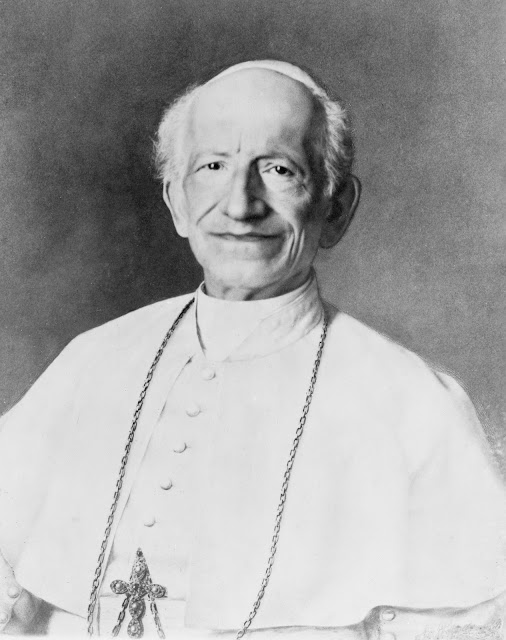

Thérèse’s Father, St. Louis Martin

One such example of these terrifying visions was

the transformation of her father’s hat, described above. Thérèse recalled

watching as her father’s lumpy, worn hat suddenly morphed into some hideous,

menacing shape.

Her father, Louis Martin—now Saint Louis

Martin—was so disturbed that he began to weep in despair. After half a year of

these unending torments, Louis was grief-stricken over the fate of his daughter.

Thérèse recalled how her father suffered greatly,

thinking that she was going to die. Louis had already lost his wife and many of

his children. Thérèse said that the Lord might have comforted her father during

this time, telling him “This sickness is not unto death, but for the glory of

God.”[5]

Of course, if Thérèse indeed had such awareness, she might also have comforted

her father.

Thérèse realized, perhaps later, that her father

did not know that “the Queen of Heaven was watching faithfully over her Little

Flower, that she was smiling upon it from on high, ready to still the tempest

just when the delicate and fragile stalk was in danger of being broken once and

for all.”

In May 1883, Louis came to Thérèse’s room to give money

to Marie, ever at Thérèse’s side, to send for a novena of prayers to be offered

for a cure at the shrine and basilica of

Notre-Dame-des-Victoires in Paris—another connection to Our Lady of Victory.[6]

Given the non-natural origin of Thérèse’s illness, it appeared that a miracle

was necessary to restore her health.

|

| Basilica of Notre Dame des Victoires, Paris |

“Yes, a great miracle, and this was wrought by Our Lady of Victories herself,” Thérèse would later write.

The Statue of the Blessed Mother

In addition to sending Marie for a novena, Louis brought

a statue of the Blessed Mother into Thérèse’s room. This would prove pivotal.

The particular statue venerated in the Martin’s

home was a copy of a much-loved statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary created in 1735

by Edme Bouchardon[7] and

later destroyed during the French Revolution. It also closely resembled the

image of the Blessed Mother found on the Miraculous Medal, which were first

created in Paris in 1832 and thought to be also inspired by Bouchardon’s 1735

statue of the Blessed Mother.[8]

It is believed that Catherine Labouré’s confessor, Fr. Jean Marie Aladel,

presented the goldsmith Adrien-Jean-Maximilien Vachette with a copy of Bouchardon’s

statue to use as inspiration.[9]

|

| The Chapel of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal, Paris: as the original Edme Bouchardon statue was destroyed in the French Revolution, this is another iteration of the original |

Moments of relief were few and far between during Thérèse’s strange and prolonged illness. Nevertheless, in those few precious moments, Therese contented herself by weaving embellishments for the Blessed Mother’s statue.

Thérèse beautifully described her beloved pastime

and the Little Flower’s “shining sun”:[10]

When my sufferings

grew less, my great delight was to weave garlands of daisies and forget-me-nots

for Our Lady’s statue. We were in the beautiful month of May, when all nature

is clothed with the flowers of spring; the Little Flower alone drooped, and

seemed as though it had withered forever. Yet she too had a shining sun, the

miraculous statue of the Queen of Heaven. How often did not the Little Flower

turn towards this glorious Sun!

The Little Flower would not “droop” and “wither

forever,” nor even much longer.

Here is the actual Our Lady of the Smile statue from the Carmel in Lisieux. It is located above the corpus and relics of St. Therese, which are pictured in the foreground of the picture on the left. These were thoughtfully contributed by a friend of mine:

The Novena Concludes & Pentecost Sunday

May 13, 1883 was another auspicious day for Thérèse.

Not only was in Pentecost Sunday, but it was one of the last Sundays of the

Novena of Sundays that her father had sought from Notre-Dame-des-Victoires. It

was also another date of Marian significance, for on this date in 34 years, Our

Lady would appear to the children of Fatima.

Marie, who rarely left Thérèse’s side had,

surprisingly, left Thérèse’s side. Marie was in the garden while Léonie, yet another

of Thérèse’s sisters, remained at her side.

Thérèse would later describe what happened next:

I began to call:

“Marie! Marie!” very softly … so I called louder, until Marie came back to me.

I saw her come into the room quite well, but, for the first time, I failed to

recognize her. I looked all round and glanced anxiously into the garden, still

calling: “Marie! Marie!”

When Thérèse still did not recognize her after

several efforts, Marie knelt down in tears at the foot of Thérèse’s bed. Marie turned

towards the statue of the Virgin Mary and begged her intercession with all the fervor

of a mother who begs for the life of her child and will not be refused.

Thérèse’s sister Léonie, later Sister

Françoise-Thérèse Martin, testified how, at that moment, all three of Thérèse’s

sisters fell to their knees filled with hope as they implored Our Lady to heal

their little sister. It is a scene reminiscent of another group of four sisters,

the March sisters of the novel Little Women, begging for the health of

their sister, Beth.

Marie, as Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart,

testified that she thought this was finally going to be the dreaded, final moment

of Thérèse’s torments. Her death. She and her sisters threw themselves “at the

foot of the statue of the Blessed Virgin,” Marie said.

Thérèse later wrote how the pleas of her sisters

were a storm sent up to Heaven:

That cry of faith forced the gates of

Heaven. I too, finding no help on earth and nearly dead with pain, turned to my

Heavenly Mother, begging her from the bottom of my heart to have pity on me.

The result of these prayers was both swift and startling, at

least for Thérèse. She wrote next how the statue of Our Lady responded:

Suddenly the statue seemed to come to

life and grow beautiful, with a divine beauty that I shall never find words to

describe. The expression of Our Lady’s face was ineffably sweet, tender, and compassionate;

but what touched me to the very depths of my soul was her gracious smile. Then,

all my pain vanished, two big tears started to my eyes and fell silently … They

were indeed tears of unmixed heavenly joy. “Our Blessed Lady has come to me,

she has smiled at me. How happy I am, but I shall tell no one, or my happiness

will leave me!” Such were my thoughts.

Thus came to be Our Lady of the Smile.

St. Thérèse is Cured

“Our Blessed Lady has come to me; she has smiled

at me,” Thérèse recounted.

It is important to remember at this point that this

was not the first time in her life that Thérèse had been brought back from the

brink of death by a miraculous cure. As is his way, St. Joseph protected the

baby Thérèse from death and the devil, preserving her to be raised in the holy

warmth of Mother Mary.

Céline later recounted this divine intervention

early in Thérèse’s life. Thérèse was dying of a fatal intestinal disorder that

had already claimed the deaths of two Martin children, but Thérèse’s mother, now-Saint

Marie-Azélie Guérin Martin, fell to her knees before another family statue,

that of St. Joseph. Azélie’s pleas before St. Joseph’s statue must have

mirrored the pleas of the Little Flower’s three sisters before Our Lady’s

statue.

Heaven responded, as it so often would when the

Martin family combined their pleas, and Thérèse survived.

And now, perhaps remembering the work of her most

chaste spouse, the Virgin Mary personally appeared to cure the Little Flower.

As if the Virgin Mary’s apparition was not enough in

itself, Thérèse further elaborated on the lasting effects of Marie’s prayers:

[Marie’s] prayers

had gained me this unspeakable favor: a smile from the Blessed Virgin! When [Marie]

saw me with my eyes fixed on the statue, she said to herself: “Thérèse is

cured!” And it was true. The Little Flower had come to life again—a bright ray

from its glorious Sun had warmed and set it free forever from its cruel enemy. “The

dark winter is past, the rain is over and gone,”[11] and

Our Lady’s Little Flower gathered such strength that five years later it opened

wide its petals on the fertile mountain of Carmel.

Not only had the warmth of the Virgin Mary’s smile cured

Thérèse, such warmth would carry Thérèse all the way to her entrance into the Carmelite

monastery. But her entrance to Carmel would be its own ordeal, requiring additional

intercession and suffering, as Thérèse resolved to enter the Carmelites at the uncustomary

age of fifteen.

A Blessing and a Curse

St. Thérèse had resolved to tell no one of her miraculous

experience, writing “How happy I am, but I shall tell no one, or my happiness

will leave me!”

Thérèse’s vision had lasted for over forty minutes.

It may have felt like just a moment to Thérèse, but she had been transfixed on

the statue for a substantial amount of time. Her sisters noticed.

After the apparition, Thérèse looked around at her

sisters, and “recognized Marie; she seemed very much overcome, and looked

lovingly at me, as though she guessed that I had just received a great grace.”

Marie soon asked Thérèse to reveal what had

happened. She fully believed the Blessed Mother had appeared to Thérèse. The Little

Flower admitted that she “could not resist her tender and pressing inquiries.”

Thérèse waited until she was alone with Marie. She

told Marie that she was astonished that Marie knew her secret, even though she

had not said a word. Thérèse then divulged what had happened and how the

Blessed Mother had smiled at her. After she told Marie the details, though, her

joy soured: “Alas! as I had foreseen, my joy was turned into bitterness. For

four years the remembrance of this grace was a cause of real pain to me.”

Marie was bursting with excitement over the

Blessed Mother’s miracle and apparition. This is, of course, a very understandable

sentiment. And yet, the devil seemed to turn it to his advantage.

Marie begged Thérèse for permission to share her secret

with the nuns at the Carmelite monastery. Thérèse found she could not refuse

her sister. When Thérèse first visited Pauline again after her dramatic

recovery, she was initially overflowing with joy at seeing her sister clothed

in the habit of Our Lady of Carmel. “My heart,” she said, “was so full that I

could hardly speak.”

Then, things soured as Thérèse was questioned by the

other Carmelite nuns:

Some

asked if Our Lady was holding the Infant Jesus in her arms, others if the

Angels were with her, and so on. All these questions distressed and grieved me,

and I could only make one answer: “Our Lady looked very beautiful; I saw her

come towards me and smile.” But noticing that the nuns thought something quite

different had happened from what I had told them, I began to persuade myself

that I had been guilty of an untruth.

Though Thérèse lamented the loss of the happiness that the appearance

of Our Lady of the Smile had given her, she mused also on the purpose of such

loss:

Our Lady allowed this trouble to befall me for the good of my soul;

perhaps without it vanity would have crept into my heart, whereas now I was

humbled, and I looked on myself with feelings of contempt. My God, Thou alone

knowest all that I suffered!

This period of humility, while formative, would not continue

unabated forever. It would be four years:

For

four years, the remembrance of this grace was a cause of real pain to me, and

it was only in the blessed sanctuary of Our Lady of Victories, at my Mother’s

feet, that I once again found peace. There it was restored to me in all its

fullness, as I will tell you later.

At the Basilica of Our Lady of Victories

It was the early morning 4th November 1887,

and the Little Flower and her family were passing alone through the silent streets

of Lisieux to the train station.[12]

They were leaving on a pilgrimage to Paris and Rome.

Each of the train compartments bore the name of a

saint. The Martin family’s compartment bore the name “St. Martin,” and

everybody on the pilgrimage took to calling the future St. Louis Martin by “St.

Martin.”

In Paris, Louis took his family to see all the

sights in Paris, but for Thérèse one sight overshadowed all the others: the basilica

of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires. It was at this same shrine of Our Lady of

Victories that the novena had been prayed for Thérèse’s cure at her father’s request.

And it was also at the basilica that Thérèse would

be healed a second time. All the doubts that had come to torment Thérèse following

the Blessed Mother’s apparition vanished and she once again found peace.

I

can never tell you what I felt at her shrine; the graces Our Lady granted me

were like those of my First Communion Day. I was filled with peace and

happiness. In this holy spot the Blessed Virgin, my Mother, told me plainly

that it was really she who had smiled on me and cured me. With intense fervor,

I entreated her to keep me always, and to realize my heart’s desire by hiding

me under her spotless mantle, and I also asked her to remove from me every

occasion of sin.

Thérèse’s sister Marie also testified regarding

this event: “It was at the foot of Our Lady of Victories in Paris that her

inner struggles ceased … she received confirmation … of the truth of the

vision.”

The timing of this second encounter with the

Blessed Mother was no coincidence. It prepared the Little Flower for her

meeting with Pope Leo XIII when the pilgrimage reached Rome.

Audaciously, and despite being told to say nothing

before the pope, the Little Flower made a bold request of the Holy Father:

I

kissed his foot and he held out his hand; then raising my eyes, which were

filled with tears, I said entreatingly: “Holy Father, I have a great favour to

ask you.” At once he bent towards me till his face almost touched mine, and his

piercing black eyes seemed to read my very soul. “Holy Father,” I repeated, “in

honor of your jubilee, will you allow me to enter the Carmel when I am

fifteen?”

Thérèse had made a special request to enter the

Carmelites early at fifteen years old. This request had slowly ascended the

ranks to the desk of the Bishop of Bayeaux, but there it had stalled. Emboldened

now by the Blessed Mother, Thérèse decided to make her appeal directly to the

pope.

What was the pope’s response?

After some explanation from the Vicar-General of

Bayeaux and a second plea from Thérèse, the pope responded, “Well, well! You

will enter if it is God’s Will.”

Thérèse was ushered away before she could make a

third plea, but within a month, on December 28, the Feast of the Holy

Innocents, the Bishop of Bayeux granted Thérèse’s special request and authorized

her “immediate entry into the Carmel.”[13]

The rest, as they say, is history.

Prayer to Our Lady of the Smile

Do you feel a stirring of devotion to Our Lady of the Smile? Here is the prayer for her intercession:[14]

Prayer to Our Lady of the Smile

O Mary, Mother of Jesus,

and our gentle Mother too,

with a visible and radiant smile

you consoled and cured

your beloved child, St. Thérèse of the Child

Jesus.

We ask you now to smile on us,

amid the troubles of our lives.

May your gentle smile bring light and healing

to the darkness and disease of our body, mind and

spirit.

Instill us with hope and deepen our faith

so that we enjoy forever

your maternal and enrapturing smile in heaven.

Amen.

Footnotes: Our Lady of the Smile & St. Thérèse of Lisieux

[1] Story

of a Soul, Chapter 3: “Pauline Enters Carmel”

[2] Story

of a Soul, Chapter 3: “Pauline Enters Carmel”

[3] Dr.

Marie-Dominique Fouqueray, “A Strange Illness: The Illness of Thérèse at Age

Ten from Easter to Pentecost 1883.”

[4]

Easter Sunday was on March 25 in 1883, which happened to coincide that year

with the Solemnity of the Anunciation.

[5] John

11:4

[6]

The Basilica of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires was named by King Louis XIII, who

dedicated it to his victory over the Protestants at La Rochelle in 1628 during

the French Wars of Religion. It was not named for Our Lady of Victory.

Nevertheless, it is the same Blessed Mother interceding for both victories.

[7] 1698-1762

[8]

The Blessed Mother appeared to St. Catherine Labouré in 1830, but the first

medals were not fashioned until 1832.

[9] Descouvemont/Loose.

[10] Story

of a Soul, Chapter 3: “Pauline Enters Carmel”

[11] Song

of Solomon 2:11

[12] Story

of a Soul, Chapter 6: “A Pilgrimage to Rome”

[13] Though

the Bishop’s permission reached the Carmelite monastery in December that Thérèse

be allowed to enter immediately, the Mother Superior resolved not to allow her

entrance until the customary time during the Easter season. Thérèse describes

this in her autobiography: “You told me, dear Mother, that you had had the

Bishop’s answer since December 28, the feast of Holy Innocents; that he

authorized my immediate entry into the Carmel, but that nevertheless you had

decided not to open its doors till after Lent. I could not restrain my tears at

the thought of such a long delay. This trial affected me in a special manner,

for I felt my earthly ties were severed, and yet the Ark in its turn refused to

admit the poor little dove.”

[14]

“The Healing of Our Lady of the Smile,” Society of the Little Flower, January

9, 2021, accessed via littleflower.org.

%20Allegoria%20della%20battaglia%20di%20Lepanto%20-%20Gallerie%20Accademia.jpg)

0 Comments